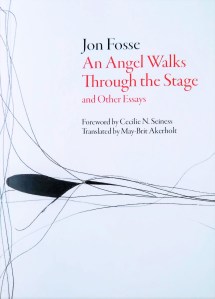

Jon Fosse; An Angel Walks Through the Stage; Trans. May-Brit Akerholt; Dalkey Archive Press, 2015

“All good art comes into being in a relationship with death, through accepting the great mysterious secret of death, and life.”

If one views art as a necessary, compulsory aspect of the human condition, then what are the depths, or located differently, perhaps the adjacent cosmic fringes, to which we will go to explore its existence? Creative output has been the greatest driving force of our species’ development for many millennia, manifested in both the practical and the secular; we have invented religious structures, re-formed nature, widened our understanding of the cosmos, and have gained deep knowledge of the material minutiae of our world. But in all this contribution, what is art? It is surely colors confined within four corners and hung on walls, texts redefining our perceptions, earth moved and formed into cohesion with its surroundings, and music that consists of 4 min. 33 sec of environmental sound. Within this we have of course Beethoven, Mozart, Arvo Part, Malevich “black squares,” epics of Hell, and much more. We poor ink, and yet more ink, into this wholly subjective arena. But perhaps there is art, product for consumption, and art, production for the sake of the ethereal, the mystical. Fosse is very much formed and concerned with this second realm and its relation to the first.

There are essays herein regarding Fosse’s ideas about voice, narrator, and the true meaning of writing, of which is movement, bringing into existence, and its relation to voice and language as a mystical endeavor. He writes of his love for one of the two official Norwegian languages and his country’s general misunderstanding of their literary master, Henryk Ibsen. These are short pieces, collected from a twenty-year span, written in a clear and sometimes conversational mode. But in these short essays, in this minimal appearing book, what permeates all is Fosse’s conviction about the “other” that is art. Mysticism is the structure on which it seems his entire view hangs. There are many references to silence, space, mystery, the sacred:

“And to me, the novel, to be obstinate, is constantly in search of the lost God,” or;

“…silent speech, full of unknown meaning,” or;

“…like a voice that comes from somewhere far away.”

It is this mystical through-line that I find so compelling here. In the version of our world that is now riddled with the media-based clichés of stimulation, information overload, noise and image bombardment, Fosse embraces silences, emptiness, repetition, simplicity. The longest essay, “Negative Mysticism,” acts as a biographic keystone to this position, where early on Fosse writes, “So silence is perhaps the best way to preserve what we know deepest down.” He expresses ambivalence about relating these ideas, but continues:

“…it is in other words the writing which has opened the religious aspects for me and turned me into a religious person, and some of my deepest experiences can, as I have gradually understood, be called mystical experiences.”

He writes of Norwegian Puritanism and Quakerism in his personal family history, refers to himself as a post-puritan. He chooses to have his novels face away from the world, to be their own universe unto themselves, and the silence and speech of Quaker practice is similar to his approach to writing. One gets the impression these are not “born-again,” expository proclamations, sharing for the sake of proselytizing, but that his positions are fibrous to his understanding of himself as an artist, and that his appreciation of art is rooted in this conviction of the spiritual-mystical. He does not come off as a guru, but as a deeply inward facing individual whose attempts at making art, the speech, silences, and movements of his texts, are forms of personal prayer.

I’m glad to have experienced these pieces as I continue to read through his work in translation. Having read Aliss at the Fire many years ago, a book that seemed revelatory at the time, a beautiful work unlike so much else I have read, I am eager to return to its austere world, with a greater understanding of Fosse’s motivations.