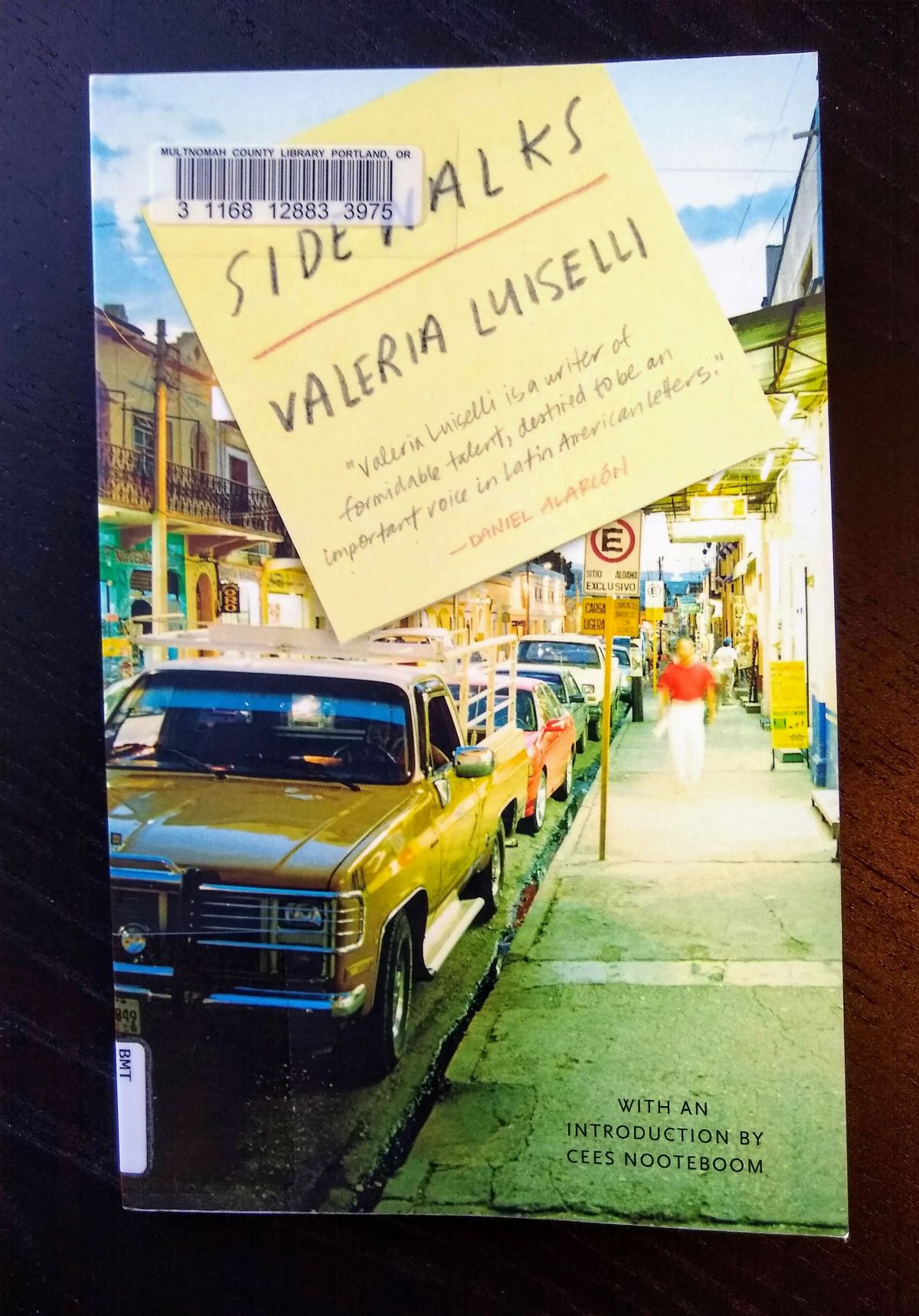

I have made a partial pivot from my current reading of Fosse, a resurfacing, so to speak, for air to fortify the next leg, only to be pulled under by a swell of a quite different system. Initially thought of as diversionary reading, these books remain on the reading tables, at hand. I have always enjoyed the simultaneous reading of non-fiction, usually unrelated histories, while reading fiction, hence the selection of essays by Isaiah Berlin. David Winters’ book Infinite Fictions I sought as a tool, a lesson in how to read and write reviews, which then led me to Warren Motte, the noted critic of French Literature. Valeria Luiselli’s Sidewalks then, when glimpsed on the shelf was irresistible in the context of current global-literary-cultural-essay immersion.

David Winters’ proves to be good company: engaging, smart, accessible, informative. His pieces in the second half of this book, responding to others’ books of criticism and literary theory are quite good. He excels in giving a good account of the work, explaining its significance or interest to him while offering reflective counter-thoughts. He handles the reviews in such a way that, indicative of the best reviewing practice, he constantly stokes the reader’s interest, and most likely, their enthusiasm to pursue the titles for themselves. His approach, namely conversational, not over-the-top clever, acts as an introductory welcome to texts that may otherwise be off the radar ( at least frequently mine), all the while he maintains a professional front; he does not fall into chatty reverence but operates in the way the best teachers do: he stokes one’s excitement by displaying his own for the material, but then encourages you to be thoughtful, reflexive.

Fables of the Novel, is a much different creation. Whereas Winters’ title is deliberately popular and constructed as accessible (reviews), Motte’s book is academic, critical, scientific. His proclivity for modern or experimental literature makes the list of titles he writes about quite interesting. As one of the leading authorities of contemporary French Literature (he wrote the first book on Georges Perec) one knows they are in capable hands. His subjects in this book include J.M.G. Le Clezio, Eric Chevillard, Marie Ndiaye, Jean Echenoz, Jean-Philippe Toussaint. The book opens thus:

Readers familiar with the contemporary novel in France are currently witnessing, I believe, the most astonishing reinvigoration of French narrative prose since the “new novel” of the 1950s.

He then relates his appreciation for a wide array of literary output, but finds plenty of worthy novels “too bland, like eating fried eggs without salt.” He is interested in the avant-garde because that is the point of exploration, newness, unmapped territory, but acknowledges that much cutting-edge work is alienating for many readers, “forbidding.” Then he goes on to describe the “avant-garde with a human face…inaugurated in the novels of Raymond Queneau, and confirmed in those of Georges Perec.” This is the novel that, while pushing the reader’s thought processes and demanding some attention, “can also be read luxuriously.”

The essays are then devoted to texts whose worlds are usually that of the quotidian, told in largely simple narrative, but he finds in them larger contemporary, exploratory themes and specifically: “Each of the novels I deal with here seems to me to present – among the many other different things they may offer – a fable of the novel, a tale about the fate of that form, its problematic status, its limits, its possibilities.” In other words, though these books under consideration may not be outwardly avant-garde in the Joycean or Pynchonesque way we have come to understand the term, their operation is that of the cuckoo, infiltrating the bastion of conventional literature, while delivering games, tricks, assaults on language and form, and in their work, posing questions about the novel itself.

Berlin was known as one of those intellectual’s that could write on history, as it relates to ideas, as it relates to culture, as it relates to politics, a kind of cultural polymath. Famous for his writings about the Counter-Enlightenment and Two Concepts of Liberty, these essays (I have read about a third so far) are fascinating in their range. Not prepared to write anything like a review for this large collection of complicated material, I will say, as an initial foray into Berlin’s work, these essays right now, act as larger framework material for interpreting what I read in international literature and the arts. His ideas about the French Revolution and rationalism versus the oppositional thinkers such as Johann Hamann and Giambattista Vico leaves a lot to be considered. This is the kind of book (a collection of his most popular/well-known writings) that gives me the sense of its long being near at hand and referenced.

Valeria Luiselli’s Sidewalks, in contrast to Berlin’s essays, is totally digestible. Physically thin at just over 100 pages and comprised of mostly short paragraphs, that is not say it is insignificant in any way. Reading this book is like being in the company of a smart, philosophical, worldly, and cool person. It is a hybrid of personal and travel essay, ruminations on melancholy, nostalgia, movement in space. Written by a young, globally-experienced person, it does not feel hip or ironic, she may even be accused of being overly pondering, the kind of “sad” that I think may annoy the large group of get-in-capitalist-mediocre-line that is represented by those of us born in the 80s, and yet, I believe she captures underlying qualities that the aforementioned generation call disconnected, depressed, romantic. It is in writers such as Luiselli and Teju Cole, those who grew up in a post-Cold War global era, that discover obstinately “antiquated” or memorializing writers such as W.G. Sebald, that may prove an interesting way forward in contemporary thought. His emphasis on exile, interconnections, fictional reality, exile, anti-tech influenced prose, and memory are the legacy that will continue to influence. Remembrance, acknowledgement, open intellectualism, depression or melancholy as a popular condition of life, hauntology, global flaneurship in contemporary capitalist-surrounded cities, acceptance of immigrant cultural contributions are subjects I see Luiselli grappling with in this book.